The Fatal Dive of Bernard Reeves in Mexico’s Deadly Cave System

| Incident Location (Country, Town/City/Region, Cave Name) | Diver Full Name (Deceased) |

|---|---|

| Sac Actun Cave System near Tulum, Mexico | Bernard Reeves |

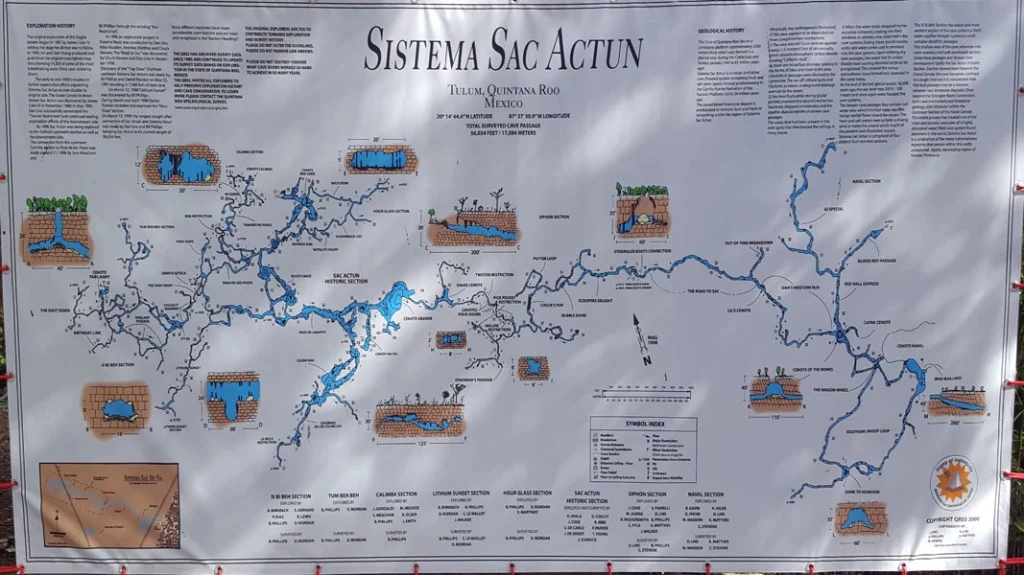

It was February 11 2013, the water in Cenote Calimba still and mirror-like. Sunlight poured through the jungle canopy, cutting bright shapes onto the surface. Beneath that beauty lay the sprawling, twisting passages of the Sac Actun Cave System — one of the longest and most complex underwater cave systems in the world.

Bernard Reeves, 48, from Montreal, Quebec, Canada, was no casual swimmer. He was a trained and experienced cave diver, confident in his skills and in the diving gear he carried: a well-fitted diving suit, a secure diving mask, and full diving tanks monitored by his diving computer.

The cave, however, was a maze of choices.

Three exits — Cenote Calimba, Cenote Box Chen, and Cenote Ho Tul — sat near one another, while another line, the Paso de Lagarto, stretched to the distant Grand Cenote.

Inside, guidelines threaded through the darkness. Some split at “T” intersections, others broke into “jumps” where divers had to connect their own reel to continue safely. The cave’s arrows pointed toward exits, but in a place with multiple exits, the meaning of those arrows could twist into deadly confusion.

A Solo Decision

Reeves was part of a group of seven divers that day. They entered through Cenote Calimba, but he made a choice before the dive began — a choice that would set him apart.

While the others planned to split into two teams of three, Reeves told them he would go solo. Before gearing up, he overheard another team talking about heading toward Cenote Box Chen.

“I’ll follow that plan too,” he said, adjusting his diving mask and checking the straps of his diving suit.

It would be his first time in that section of the cave.

Into the Darkness

The cave swallowed him quickly. His light bounced off smooth limestone walls, and the sound of his own breathing filled the silence, steady through the diving computer’s mouthpiece.

He moved ahead of the rest of the group, swimming into the winding network. The guidelines, sometimes thick with silt, stretched before him. Every so often, he would see an arrow marker pointing the way — or so it seemed.

He had his full diving tanks, but in the Sac Actun, air is just one of the things a diver must keep track of. Distance, direction, and mental clarity are just as important. One wrong choice on a “T” intersection or “jump” line could lead away from safety.

The Maze of Lines

Inside the Sac Actun, the passageways feel endless. Some sections are so narrow a diver’s shoulders nearly touch the walls. Others open into vast, silent chambers where the ceiling vanishes into darkness.

Bernard’s path took him deeper, past points where personal markers could have been placed to signal his route back. Without them, the guideline markings became harder to interpret. Was the arrow pointing to Cenote Box Chen, or toward a different exit entirely?

Far behind him, his group followed their own plans, unaware that Bernard was already somewhere ahead, navigating the cave alone.

During their dive, one of Bernard Reeves’s groups noticed the equipment he used to mark his path. After the recovery, investigators found that Reeves had actually picked up some of this gear during his attempted exit.

Thanks to this, along with data from his diving computer, they could track his entire route through the cave, even though he had been diving alone.

At a key “T” intersection on the Paso de Lagarto line, Reeves placed a personal marker — a wooden clothes pin — on the Cenote Calimba side. This marker was meant to show his exit direction. Then, he continued on the Paso de Lagarto line.

At the “jump” intersection leading to Cenote Box Chen, Reeves connected a jump reel to the line, but he did not place a personal marker on the Cenote Calimba side to mark his exit.

There, a permanent line arrow pointed toward the distant Grand Cenote exit — adding to the confusion.

Following the Wrong Path

Reeves swam toward Cenote Box Chen as planned, turning his dive around at the 40-minute mark.

But when he reached the jump reel again, he made a critical mistake. Instead of following the Paso de Lagarto line back toward Cenote Calimba, he followed it in the wrong direction — toward Grand Cenote.

He traveled about 800 feet down that path before realizing his error.

The Deadly Detour

The extra distance burned through his air supply much faster than expected.

Even though he pulled out his jump reel to try and find the right way, the damage was done. His diving tanks were running dangerously low.

In the end, Bernard Reeves was found in just 19 feet of water near the Cenote Calimba exit — too far gone to make it safely to the surface.

| Key Details | Information |

|---|---|

| Dive Date | February 11, 2016 |

| Location | Sac Actun Cave System, Mexico |

| Diver | Bernard Reeves (48) |

| Cause of Death | Drowning due to running out of air |

| Critical Error | Following wrong guideline line |

| Personal Marker Used | Wooden clothes pin |

| Depth Found | 19 feet |

Reeves’s dive is a chilling reminder that even the most skilled divers can get lost in the labyrinth of the cave — where every choice matters and every marker can mean life or death.

After the tragic recovery, the lead investigator, Phillips, carefully reviewed every detail of Bernard Reeves’s dive.

He suggested several key factors that contributed to the accident:

- The dive plan was overly complex, increasing the chances of confusion.

- Reeves was unfamiliar with this particular section of the cave, making navigation harder.

- Directional signs and guidelines at the crucial Paso de Lagarto/Box Chen jump were unclear or insufficient, causing misinterpretation.

These elements combined in a deadly way, turning what should have been a manageable dive into a fatal maze.

Complexity in the Cave System

The Sac Actun Cave System’s network of lines and “jumps” demands exacting precision. Even experienced divers like Reeves rely heavily on clear directional referencing and proper use of personal markers to find their way back to safety.

When those signals aren’t obvious — or when a diver tries to navigate unfamiliar passages alone — the risk skyrockets.

| Contributing Factors to the Accident | Description |

|---|---|

| Overly Complex Dive Plan | Too many navigation decisions in one dive |

| Unfamiliarity with Cave Section | First time diving near the Box Chen jump |

| Unclear Directional Referencing at Jump | Permanent arrows and markers caused confusion |