Lost in the Depths: The Tragic Tale of Kent Maupin and Mark Brashear at Jacob’s Well

| Incident Location | Diver Names |

|---|---|

| Jacob’s Well, Wimberley, Texas | Kent Maupin, Mark Brashear |

Two friends decided to dive into the Waters of Jacob’s Well in the company of others without information for their dive group. They decided to dive deeper into the most dangerous parts of the cave without backup lights or guidelines. They went in through a tight passage and disappeared into a dark tunnel, while their friend anticipated their return.

The Enigmatic Jacob’s Well

Jacob’s Well is a natural spring that is active all year and is found in the Texas Hill Country. The water flows from Cypress Creek’s bed, and the spring is situated to the northwest of Wimberley, Texas. The Hayes County Parks Department manages the area where the spring is located, which is called Jacob’s Well Natural Area.

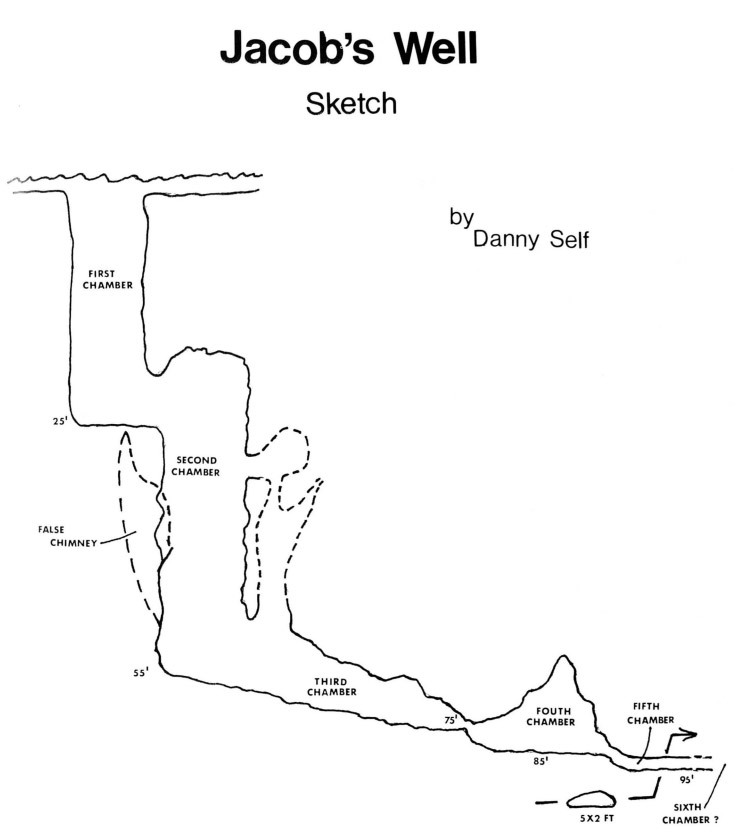

The spring’s mouth is 12 feet in diameter and is a popular swimming spot for locals. The opening of the spring in the creek bed leads to Jacob’s Well cave, which descends vertically for approximately 30 feet before continuing downward at an angle. The cave consists of a sequence of silted chambers divided by narrow restrictions, culminating in an average depth of 120 feet.

Cave Diving Risks and History

Before modern times, the natural Artesian spring, which is fed by the Trinity aquifer, spewed water from the cave’s opening. Cave divers from the Jacob’s Well Exploration Project have explored and mapped the system, revealing that it comprises two main conduits. The first passage stretches roughly 4,500 feet from the surface and reaches a maximum depth of 137 feet. The second passage diverges from the primary conduit and is approximately one thousand feet long. While the cave is a popular destination for open water divers, not all of them have the necessary training or equipment for cave diving, which has led to nine deaths at this location between 1964 and 1984.

Kent Maupin and Mark Brashear’s Fateful Dive

Kent Maupin, a seasoned diver, was friends with Mark Brashear, a San Jacinto College student. Kent had often talked about diving into the last chamber of Jacob’s Well, which had a notorious reputation. Despite the risks, Kent was determined to go beyond the safe point and explore further. Kent and Mark joined a group of divers from Pasadena and camped out at Jacob’s Well in Wimberley. In the late hours of September 9, 1979, Kent, Mark, and a few others went for a dive into the well, heading towards the much-avoided fourth chamber.

A Dangerous Descent and Tragic Consequences

The first chamber of Jacob’s Well descends straight down about 25 feet, followed by the second chamber going down an additional 35 feet. The third chamber slopes gradually, narrowing to a depth of 75 feet. At the end of the third chamber, there’s an opening that leads to the fourth chamber. Several people who ventured into the fourth chamber before had not returned alive. On that fateful night, the two young men were observed at the entrance to the chamber, moving back into the opening and dragging their tanks along with them. They didn’t have any backup lights or safety lines, seemingly motivated only by an impulse to explore further.

Kent removed his tank back into the narrow passage and pulled the tank behind him. Mark did the same. Joe saw Mark disappear into the tunnel. Joe was taken aback because nobody had talked to him about it. He signaled his light back and forth, attempting to get Mark’s attention, but Mark wouldn’t look up at him. He just gazed down at his tank and pulled it with him into the darkness.

Joe was aware that Kent and Mark’s steel tanks held less air than his aluminum ones, and since they were deeper, their air consumption would be greater. As Joe began to run low on air himself, he realized that the situation was serious. He tried to get their attention by banging on his tank with his knife, but he received no response.

Joe left his light shining in the passage, hoping they would follow it to find their way out. After he surfaced, the clear water of the well turned murky, which could have been caused by either a gravel slide or two panic-stricken divers stirring up silt. Joe knew that it was highly likely that Kent and Mark had died.

Don Dibble and Paul Battaglia were informed of the accident by a San Marcos police officer and arrived at the scene soon after. Don was a former Navy diver with the highest rating in the Professional Association of Diving Instructors. Despite knowing that there was no chance of finding the divers alive, they attempted to rescue them anyway. They called two other members of the Hayes County Volunteer Body Recovery Unit, collected some equipment from Don’s dive shop, and headed to Wimberley.

They found the exhausted and shocked group of surviving divers who had unsuccessfully searched for the bodies since the accident. One of the divers claimed to have seen the bodies buried beneath a pile of gravel. Don observed the well, which was a black hole at that hour, and decided to wait until the morning before attempting the recovery. He called the dead ex-persons in his private language, indicating that they could wait until daylight.

However, as it was already dark in Jacob’s Well, if the bodies were visible, it would not be an easy recovery. Don instructed two divers to descend and evaluate the situation to determine whether the recovery process would be as easy as he had been led to believe. Unfortunately, the divers were unable to see the bodies, and the passage was almost entirely blocked by gravel.

When they returned to the surface, they were anxious about the situation because that section of the cave floor was steep, and a large amount of unstable gravel was set to tumble down and bury anyone in its path. Dom decided to return to San Marcos, assemble a larger crew and more equipment, and return during daylight. They returned to the well at 10 o’clock in the morning, and two divers carefully began to move the gravel through the passage using trowels to create an opening large enough for them to pass.

However, this process only made the already terrible conditions worse. Don decided to go down into the well himself after receiving different reports about the feasibility of the recovery mission. He was accompanied by a game warden named Calvin Turner, and they left spare tanks at 25 and 75 feet while reeling out safety lines as they descended further into the well. They shone their lights upward into the ceiling crevice of the third room to ensure that the bodies were not floating above them.

The entrance where the two divers had last been seen was still blocked. Don checked his submersible pressure gauge and found that he had 1,100 pounds per square inch of air left, which would last about 10 minutes at that depth. He cautiously placed his head and shoulders into the entrance, holding on to the safety line with one hand and shining his light ahead with the other. He saw nothing but small pieces of gravel, which struck his mask lens due to the water’s flow through the constriction.

Gravel Bed

Don realized that removing the bodies would not be possible unless the unstable gravel bed was cleared. He also became aware of the danger he was in, but it was too late. He became trapped in the passage entrance due to a slide of gravel. The water became murky, and Don was unable to see. His arms were stuck, and he could not signal Turner or bang on his tank. As he struggled to free himself, his breathing rate increased, and he quickly ran out of air.

Don came to the realization that he was about to die, but he remained calm and tried to die quietly. Don was uncertain about the process of drowning and how it led to his death. He thought that he could hasten the process by either inhaling or drinking water. However, he realized that inhaling water would cause him to panic and thrash, which would lead to embarrassment for his wife. Therefore, he chose to drink the water that was suffocating him. As he took a few gulps, he felt dizzy and accepted his fate.

Suddenly, an involuntary reflex seized him, and he thrashed around, freeing himself through his flooded mask. He saw Calvin offering him the regulator from the spare tank. He took it and breathed in the air with relief. Don’s problems started when he breathed in too much air while diving. The excessive intake of air caused some of it to enter his stomach instead of his lungs. As he rose to the surface, the decreasing water pressure made the trapped air expand.

Don attempted to release the air by burping, but he was unsuccessful. He realized that if he did not ascend to the surface quickly, he would be at risk of getting decompression sickness, along with his current predicament. Therefore, he continued to ascend while experiencing unbearable pain due to the expanding gas. By the time he surfaced, he appeared to have been pregnant for nine months.

Don removed his breathing regulator and let out a scream. He didn’t feel any better until 12 hours later. His diving injury was a rare sight, and nobody had ever witnessed anything like it before. They thought it was some form of embolism, which is a common condition when expanding air becomes trapped in the lungs. The recommended treatment for this is a simulated dive in a recompression chamber. So Don was taken to Brooke Army Medical Center’s chamber. Unfortunately, the treatment did not alleviate his severe pain.

It wasn’t until later, when Don was taken to another hospital, that a doctor ordered X-rays and discovered that his stomach wall had ruptured, causing peritonitis. Don should have already died from the condition, which was equivalent to having five ruptured appendices. When the surgeon opened his swollen abdomen, it was like cutting into a basketball.

During Don’s recovery from his surgery, the search for the missing bodies continued. They brought in a well-regarded diver from Austin named Don Brod, who was 46 years old. He was known for being gruff and opinionated and had a deep fascination with Jacob’s Well since he was a boy in El Campo. Rod dove down to the opening of the last passage and peered inside. He saw Dibble’s light where it had been dropped, and behind it was a corridor filled with gravel that he believed held the bodies.

Rod realized that Kent and Mark had to excavate the tunnel by shoveling the loose gravel behind them, putting their lives at risk for the sake of exploring a few more square feet of submerged limestone. Rod concluded that the only safe way to retrieve the bodies would be to airlift all the gravel out of the cave, starting from the top of the slope and working down.

Two days later, a flatbed truck carrying a white recompression chamber in the shape of a space capsule arrived at Jacob’s Well. The chamber belonged to Schaefer Diving Company, which was hired by the families of the victims to retrieve the bodies. The owner of the company, Louis Schaefer, was optimistic about the operation’s success and was the first diver to go down. After descending into the water, he remained visible from the surface until he reached the juncture at 25 feet, where he exclaimed, “God Almighty,” upon seeing the entrance to the final passage.

Later that afternoon, Louis’s divers used a large hose to suck out gravel from the 60-foot level and spew it into Cypress Creek downstream from the well. The divers also put larger rocks into burlap bags that volunteer scuba divers tied to ropes and hauled to the surface. However, the work proved difficult, as for every foot of gravel removed, another was replaced. Nevertheless, they persisted in their efforts.

After some time, the search operation was stopped due to a lack of funds. For two days, when the divers resumed their work, they found that the opening they had spent a week clearing had almost closed up again in the two days they were away. They were back where they had started, with the dangerous and exhausting task that could last for weeks or months, and they were now working without pay. Their effort was fruitless.

Another group of divers from Brown and Root, sent by Chet Brooks for a second opinion, confirmed what Louis’s divers had eventually admitted to themselves. The best course of action was to leave the bodies where they were and seal off the well. So, 12 days after Kent Maupin and Mark Brashear perished in Jacob’s Well, the search for their bodies was terminated.

Don tried to close off the depths of Jacob’s Well by constructing a rebar and quick-set concrete grate at the entrance to the third chamber after his recovery from the hospital in January 1980. However, six months later, the grate was discovered and dismantled. It was revealed that some divers, who came equipped with the necessary tools, removed the grate and left a message for Don on a plastic slate that read, “You can’t keep us out.”

After a decade since the tragic incident, most of Mark’s remains were found, but Kent’s body was never recovered. Exactly 21 years later, Kent’s remains were finally discovered, which would give his family the closure they had been seeking all this time, and he will be laid to rest.

FAQ

Jacob’s Well is a natural spring located in the Texas Hill Country, near Wimberley, Texas. It is a popular swimming spot and features a cave system that descends vertically and then continues at an angle.

Cave diving at Jacob’s Well can be dangerous, especially for those without proper training and equipment. The cave has narrow passages, silted chambers, and restricted areas, increasing the risk of accidents and entrapment.

Kent Maupin and Mark Brashear went on a fateful dive at Jacob’s Well. They ventured into the dangerous parts of the cave without backup lights or safety lines. Unfortunately, they got separated from their friend and never returned.

Mark’s remains were found after a decade, but Kent’s body was never recovered until 21 years later, providing closure to his family.

Several search and recovery operations were carried out, involving divers and specialized equipment. Despite their efforts, the difficult conditions in the cave and the constant shifting of gravel made it extremely challenging to retrieve the bodies. Eventually, the search was called off, and the well was sealed off.