Tragedy in Roubidoux Spring Cave: The Fatal Dive of Steven Wyra

| Incident Location | Diver (Deceased) |

|---|---|

| United States, Missouri, Roubidoux Spring Cave | Steven Wyra |

Three experienced divers—Steven Wyra (age 50), Ron Shirley, and John Davis—stood at the entrance to Roubidoux Spring Cave in Missouri, preparing for a challenging and carefully planned expedition. Steven, a seasoned diving enthusiast, conducted one last inspection of his diving gear alongside his companions.

Each diver wore specialized diving certifications clipped to their gear bags, proof that they had met the strict access requirements for this difficult dive. Roubidoux Spring Cave was notorious among the diving community. It demanded not only certification but also experience and precision.

Mission Objective: Explore “The Big Room”

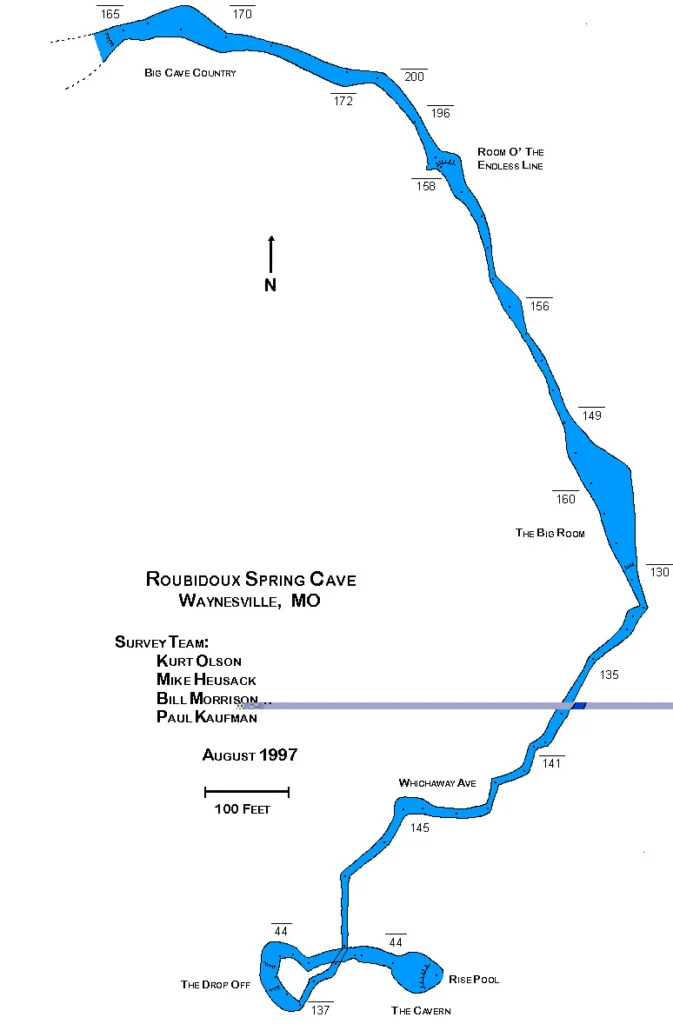

Their goal was to reach the fabled Big Room, a massive chamber hidden deep within the cave system. It was located approximately 1,400 feet (427 meters) from the cave entrance, at a depth of 165 feet (50 meters).

This kind of advanced cave diving was not for beginners. It required detailed planning, deep-water skills, and full mastery of the equipment. The three men had studied maps, reviewed dive tables, and aligned their schedules to make this trip possible.

“Roubidoux Spring Cave wasn’t for beginners.”

Dive Planning and Equipment

The dive plan was methodical. To ensure safety, they would use specific breathing mixtures suited to each phase of the dive, employ underwater propulsion devices (commonly known as scooters), and follow a staged decompression strategy to avoid the dangers of rapid ascent.

They wore dry suits to protect themselves from the cave’s frigid 50°F (10°C) water. Unlike wet suits, which allow water in, dry suits seal out all moisture. Underneath, they layered thermal clothing to retain body heat throughout the long dive.

Key Equipment Used:

- Diving dry suits – Provided full-body insulation and dryness

- Diving tanks with Triix – A breathing gas blend of oxygen, nitrogen, and helium

- Stage bottles – One with Triix and another with nitrox (oxygen + nitrogen) for decompression and ascent

- Underwater scooters – Allowed fast travel and reduced air consumption

- Diving computers – Monitored depth, time, and gas mixes

- Diving masks – Provided clear underwater vision

- Guideline reels – For maintaining orientation in low visibility

Steven had never used a scooter before and looked forward to the new experience it promised—enhanced speed and maneuverability within the submerged passages.

Submersion and Entry

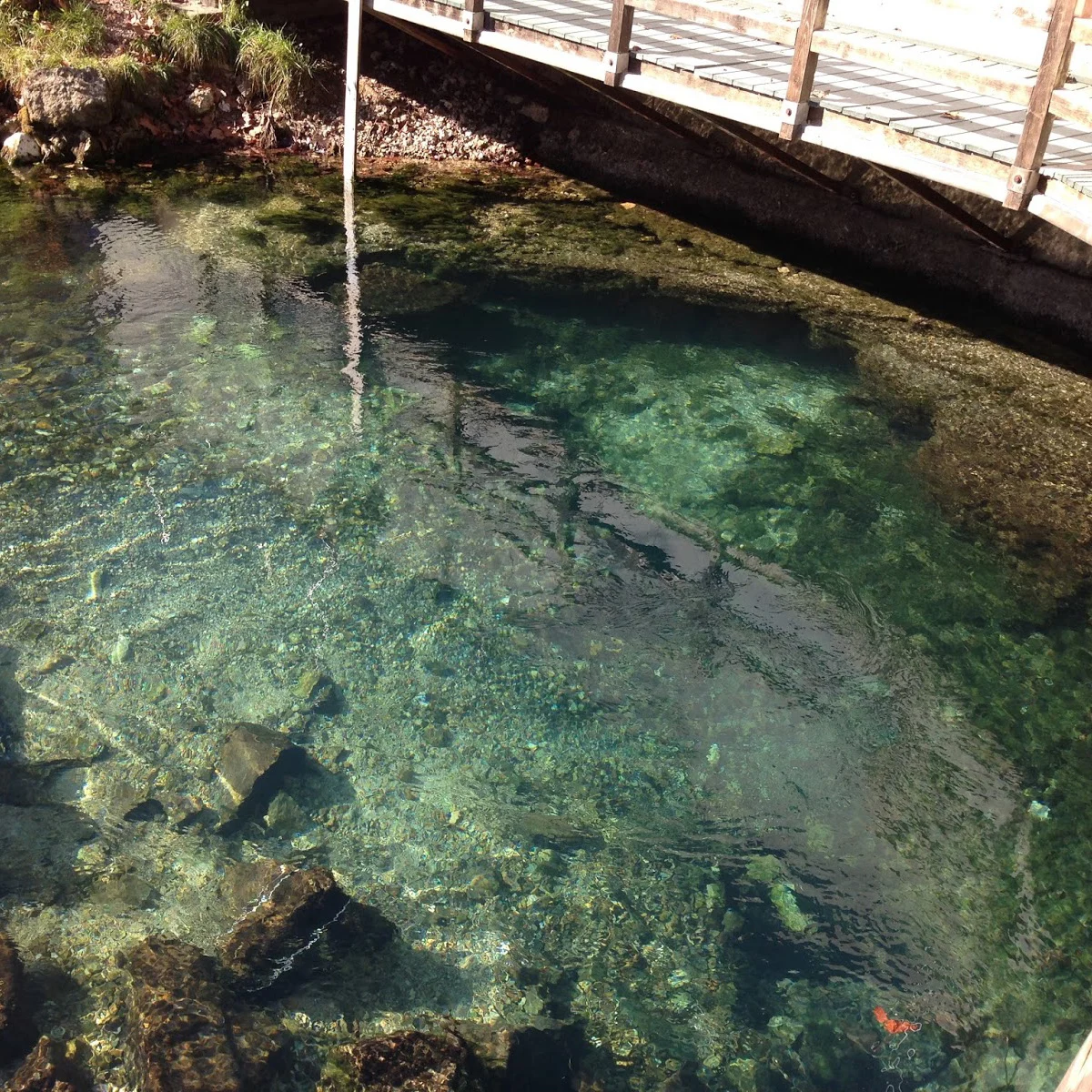

They slipped into the water, and the calm surface shimmered before settling. The spring’s entrance pool was pristine, mirroring the blue sky above. But this visibility would soon vanish as they moved deeper into the cave, where even a single misplaced fin kick could stir silt into a blinding cloud.

Phase One: Reaching the Drop-Off Room

Their initial target was a chamber known as the Drop-Off Room, situated about 350 feet (107 meters) into the system at a depth of 50 feet (15 meters). Here, the cave floor fell sharply from 50 feet to about 135 feet (41 meters), leading to the deeper tunnel system.

Their steps were as follows:

- Begin breathing from nitrox tanks

- Swim to the Drop-Off Room

- Leave nitrox tanks at this waypoint for use during their return

- Switch to Trimix travel tanks for deeper sections of the dive

Scooter Travel through Witchaw Avenue

From the drop-off, the plan called for activating their underwater scooters and navigating through a tunnel called Witchaw Avenue, a narrow and long passage that extended about 1,100 feet (335 meters) toward the Big Room.

Witchaw Avenue was an especially demanding section of the cave, with an average depth of 150 feet (46 meters). The ceiling clearance narrowed to 4.5 feet (1.4 meters) in some areas, requiring careful maneuvering. To stay on course, they relied on a permanent guideline beginning about 75 feet (23 meters) from the entrance, which served as their only reliable path through the darkness.

With a soft hum, the scooters engaged, pulling the divers smoothly through the water. Their diving lights cut through the blackness, illuminating thousands of years of limestone formations—mineral structures shaped slowly by water over millennia.

After traveling through the upper tunnel for 350 feet (107 meters) at around 45 feet (14 meters) deep, they reached the Drop-Off Room. Here, they followed their plan precisely, placing a tank at 70 feet (21 meters) for the journey back.

Decompression Planning and Deeper Descent

At the 70 ft (21 m) waypoint, the divers had strategically placed tanks for their decompression stops, a crucial step to safely return from deep dives. These tanks would be essential during their ascent to prevent decompression sickness. With that preparation complete, the trio proceeded deeper into the underwater tunnel known as Witchaw Avenue.

The tunnel became more confined as they advanced. At times, the ceiling dropped low enough that they had to tilt their heads downward to avoid striking it. Despite the limited space, their diving lights revealed otherworldly rock formations and glimpses of cave-adapted wildlife, uniquely evolved to survive without light.

First Signs of Trouble

Unnoticed by Ron and Jon, Steven began experiencing issues. His stage bottle was depleting faster than anticipated. The cause was unclear—possibly related to the additional air demands from managing the scooter for the first time, or potentially due to an equipment fault.

Rather than alerting his companions, Steven quietly switched to his back-mounted tanks earlier than planned. He pressed on with the group, determined to reach their destination: the Big Room.

Arrival at the Big Room

The Big Room soon came into view—vast and awe-inspiring, a stark contrast to the cramped tunnel they had traveled through. Even with their strongest diving lights, they couldn’t illuminate the entire chamber. For a moment, the divers paused, taking in the beauty of this rarely seen underwater cathedral.

“Few humans had ever laid eyes on this remote underground wonder.”

However, the reality of limited air supply and the long return journey demanded their attention. With mutual signals, the group began their retreat.

Dangerous Readings

As they moved back through Witchaw Avenue, Steven checked his pressure gauge. The needle was hovering at just 500 PSI, dangerously low compared to the standard starting pressure of 3,000 PSI (207 bar).

This meant Steven had consumed nearly 85% of his air supply. Understanding the gravity of the situation, he immediately signaled Ron and showed him the gauge. Ron responded quickly, offering his extra regulator, connected to a long hose specifically designed for air-sharing emergencies.

Emergency Protocol in Action

This swift and practiced response was an example of the robust safety protocols used by experienced cave divers. Now breathing from Ron’s tank via the extended regulator hose, Steven was temporarily stabilized and continued swimming alongside his friend.

New difficulties soon arose, however. Steven began having serious buoyancy issues—a diver’s ability to maintain consistent depth. He would float upward uncontrollably, then sink too low, creating erratic movement and complicating progress through the confined passage.

Separation and Escalating Trouble

Meanwhile, Jon remained unaware of Steven’s struggles and continued ahead. Despite the mounting challenges, Steven and Ron reached the end of Witchaw Avenue at a depth of 135 ft (41 m) and began ascending toward the Drop-Off Room.

As they approached 100 ft (30 m), Steven’s buoyancy worsened dramatically. He floated upward too quickly, reaching the maximum range of Ron’s long hose. The regulator was abruptly pulled from Steven’s mouth.

In the dim, murky water, Steven managed to swim back down to Ron and take the backup regulator. He signaled the universal “OK” hand gesture to reassure Ron, who then tried to recover his primary long hose regulator.

When Ron looked back up, Steven had vanished.

Zero Visibility and Vanishing Diver

The commotion had disturbed silt on the cave floor, clouding the water and reducing visibility to near zero. Ron, now increasingly concerned, ascended to the 70 ft (21 m) decompression stop, where they had left their bottles.

Jon had already passed through and retrieved his bottle. Steven’s decompression bottle, however, remained in place next to Ron’s.

Realizing something was terribly wrong, Ron collected his tank and began swimming toward the entrance, clinging to the hope that Steven had encountered another group of divers he had glimpsed earlier.

Rescue and Tragic Discovery

At the surface, Ron immediately reported the emergency—Steven was missing. Rescue divers entered the cave quickly and made a tragic discovery. Steven’s body was found floating near the ceiling of the cave, in the same area where Ron had last seen him.

All three of Steven’s diving tanks were empty. Investigators also noted that the exhaust valve on his dry suit was completely closed—a critical oversight that likely contributed to his uncontrollable buoyancy.

Lessons from a Cascade of Errors

The dive that had begun with precision and promise had ended in heartbreak. A subsequent analysis uncovered a chain of small failures that compounded into a fatal situation:

- Steven’s regulator may have been set too sensitively, causing an unnoticed air leak.

- The noise from the scooter might have masked the sound of escaping air.

- The closed exhaust valve on his dry suit prevented buoyancy control.

- Most significantly, there was insufficient communication among the divers about the seriousness of Steven’s condition.

“This unfortunate event highlighted the unforgiving nature of underwater cave exploration.”

Even for divers with proper certification, experience, and training, the dangers of cave diving are unrelenting. Steven’s tragic experience serves as a stark reminder of the importance of:

- Strict adherence to safety protocols

- Constant clear communication

- Complete equipment familiarity

- The willingness to abort a dive at the first sign of trouble