Tragedy in the Depths: The Calavera Cenote Incident

| Incident Location | Diver Full Names |

|---|---|

| Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, Calavera Cenote | Unknown |

Note: The names of the involved were changed to protect the victims. In 1995, a group of eight trained divers gathered in Tulum, Mexico for an exciting day of cave diving. They submerged below Tulum into the underground caverns and traveled through the columns and walls of limestone. By the end of the day, only five divers would make it back to the surface alive.

The Peninsula of Yucatan and the Cenotes

The peninsula of Yucatan, located in the southern region of Mexico, is home to over six thousand cenotes—caves filled with crystal clear water. Because of their beauty and proximity to the Caribbean coast, they’ve become a major tourist destination, attracting divers from around the world, beginners and experienced alike.

The name “cenote” comes from the Mayan language, meaning “water well.” These wells were considered vital and sacred to the Mayan people—they were a source of water, a source of life. The Mayans also used them as a portal to speak to the gods. In fact, the skeletal remains of over 120 people were found in one cenote alone, although it is unknown when and how they died.

The cenotes connect to an underground cave system, a labyrinth of kilometers-long tunnels. All of these systems, at some point, connect to the sea. This provides the cenotes with a mix of both fresh water from rainfalls and saltwater from the ocean. The zone in which fresh and salt water meet is known as the halocline. It creates a murky and dense blur that distorts a diver’s view.

Cave Diving in Cenotes

Diving into the caverns of a cenote is what’s known as cave diving. It’s classified as an overhead environment dive, meaning there are structures above you. This differs from standard scuba diving or open water diving, in which all you need to do is travel up to the surface. In overhead environment dives, you have to either go forward, go backward, or hope that there’s a sliver of an air pocket in case you run into trouble. It requires different types of equipment. This difference is what makes cave diving so dangerous, especially for those not trained in it.

Choice and Danger

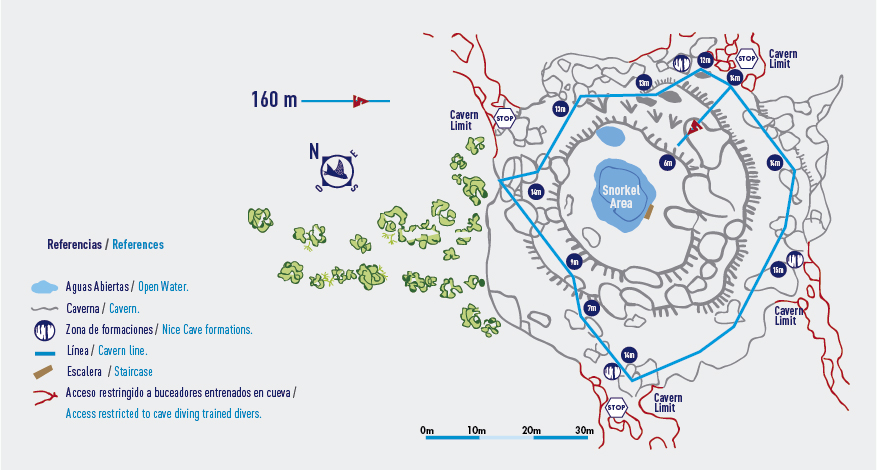

Once you begin to dive into the cenotes of Yucatan, you’re given a choice. You can stay within the limits of the cavern lines, which are permanent rope guidelines, or you can travel further into the cave system. If you choose to travel beyond the main cavern limits, there is a chance you may not make it back to the surface.

The Summer of 1995

The summer of 1995 was a busy one for Maria and her husband Harry. Their dive shop in Cozumel, Mexico had received several calls looking for a guided tour of the Yucatan cenotes. They began planning the logistics of such a tour. Though they were trained open water divers, Maria and Harry had no experience in cave diving. They decided to hire a guide or dive master local to the area they would explore—Tulum. They found one—an open water instructor. He agreed to take the group of two to his favorite cenotes that he was familiar with.

August 17th, 1995

With a tour guide in place and the diving location set, all that was left to do was wait. On August 17th, the group of eight divers met at Gran Cenote, five kilometers north of the town of Tulum. Along with Harry, Maria, and Juan, were three Dutch, an Italian, and an American woman. Though trained in open water, none were certified for cave diving. The divers strapped on their equipment, jumped into the open mouth of the cave’s entrance, and traveled into the clear blue waters below. The waters were warm, and the depths relatively shallow. The group was filled with excitement—they were diving in such a place of beauty. This may have been the most beautiful dive they had been on their entire life. Juan had made this happen. They respected their dive master and placed their trust in him.

Gran Cenote and Cenote Calavera

After spending almost an hour at Gran Cenote, they were ready for their next dive. Just south of Gran Cenote was Cenote Calavera, or the Temple of Doom. The group piled out of their taxis and approached the entrance. In front of them was what looked like a giant skull—a large mouth-like entrance with two smaller holes behind. After a resupply and re-equip, they began, one by one, to jump into the mouth of the skull and down into the water below. Looking back, they saw the sun shine through the openings—a beautiful sight.

The Journey into the Cenote

Underwater, a ladder, which looked like it had been put there by the Mayans themselves, was the only exit. Juan led the group of eight through the main section of the cenote, while Harry took up the rear. The main section was a large 360-degree area with a radius of around 366 meters. The floor reached a depth of 14 meters. Many tourists and even experienced divers stay within the cavern limits, but Juan had other plans. As they traversed further into the caverns, they became surrounded by limestone walls and columns, dripping from ceiling to floor. This was no open water dive. Juan led them further, and they traveled into the Madonna Passage, a tunnel leading to the kilometers-long cave system. The tunnel was past the main caverns, past the guidelines, and past the sign reading: “Stop! Prevent Your Death. Go No Further.”

Panic and Tragedy

They were not far into the passage when Harry, moved by panic or premonition, retreated back to the entrance. None of the other seven noticed he was gone. Juan, despite his responsibility, never looked back. The further they went, the colder it got, and the harder it became to see due to dwindling light and halocline interference. All the while, their oxygen supply was continually decreasing. The group continued swimming, beginning to panic, frightened by the diminishing oxygen. They were unsure if they were being led on an adventure or led to their death.

The Rescue Attempt

After several minutes in the passage, Juan finally looked back at the group and noticed that only three divers were left with him. They were low on oxygen; he himself was low on oxygen. Harry waited at the entrance for his wife and the others. It seemed like hours had passed—should he go back down? Then a diver resurfaced—it was the Italian. Then two more Dutch divers. Without explaining, Juan took Harry’s partially full tank and traveled back down to the passage. Every second mattered. He swam through the main cavern, through the columns and walls, arriving at the signs at the entrance. He saw that the seconds no longer mattered—two divers out of air, two divers dead. There was no more hope for them. He knew there was one left. He traveled further down the passage, between the walls. He found them—the third diver. It was Maria. She was out of air but still alive.

Tragic Outcome

Harry was now outside the entrance, fearing that his wife was gone. He continued looking back at the ladder leading into the skull’s mouth, waiting. The three minutes continued to pass by when the splash of a diver surfacing caused Harry to rush to the opening. Juan swam to the ladder, carrying Maria. She was not breathing. He quickly pulled off her equipment and began CPR. A vehicle arrived to rush Maria to the Red Cross station in Tulum. There was hope, but Juan was seconds too late for Maria too. She was pronounced dead at the station. Juan retrieved the bodies of the other two divers—one of the Dutch tourists and the American woman.

Aftermath

Juan was never charged with a crime, though many believe his actions should be considered manslaughter. He took a group of divers into dangerous caverns without the proper equipment and without the proper training. The deaths led to pain and anger throughout the Yucatan Peninsula. Dive shop owners and instructors in Yucatan and Cozumel were outraged by the incompetence of Juan. They were moved to action. They formed an association to develop a list of safety policies and procedures for diving in the cenotes. Those policies have influenced the training and practices of instructors and shops throughout the area.

The Dangers of Cave Diving

This story is unfortunately not unique. So many divers have suffered the same fate underwater, especially in the cenotes of Yucatan, where divers—many untrained and inexperienced—continue to lose their lives to this day. The number one cause of death for cave diving is suffocation, which amounts to two things: improper gear and improper training. Without the right training, you can get lost and find yourself surrounded by the unknown walls and caverns underwater, becoming disoriented and never making it to the surface again.

A Word of Caution

So, next time you find yourself underwater, looking down a dark tunnel and at a sign that reads, “Stop! Prevent Your Death,” you might consider heading back to the surface before your oxygen tank runs empty.

Before your next dive, consider insurance – it’s like having a dive buddy for unexpected challenges. Dive safe, dive covered. Explore options here

FAQ

Cave diving is a type of underwater diving that takes place in caves or cavern systems. It is considered an overhead environment dive, which means there are structures above you, unlike open water diving.

Cenotes are caves filled with crystal clear water that can be found in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. They are connected to an underground cave system and are considered sacred and vital by the Mayan people. Cenotes attract divers from around the world.

Cave diving is dangerous due to the overhead environment, where you have to navigate through tunnels and structures. The main risks include becoming disoriented, running out of oxygen, and getting trapped. Improper gear and lack of training are significant factors leading to accidents.

In 1995, a group of eight divers went cave diving in Tulum, Mexico. Led by a guide who lacked proper cave diving experience, they ventured beyond the main cavern limits. Panic and diminishing oxygen supply caused tragedy, resulting in the loss of three divers’ lives.

Proper training and appropriate gear are crucial for cave diving safety. Divers should stay within their certified limits and avoid venturing into unfamiliar caves without experienced guides. It’s important to heed warning signs and prioritize personal safety, returning to the surface before oxygen runs out.